Black History Facts

The Saga Of

The Runaway Slave

During the 19th century, the northern exodus of runaways increased as slavery was abolished in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, the New England states, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan. Those who succeeded in making it to freedom usually came from the Upper South states of Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri.

The routes they took after crossing into free territory varied. One corridor led to Philadelphia, through eastern Pennsylvania, and on to New York and Boston. Some came into western Pennsylvania and moved north before entering western New York. Others crossed the Ohio River at Louisville or Cincinnati and journeyed overland to Cleveland, getting assistance along the way in Oberlin, Xenia, and other towns. More than a few found refuge in all-black communities in Ohio’s Brown and Mercer counties. Fugitives also went to Quaker areas like Richmond, Indiana, and to larger cities such as Indianapolis and Chicago.

In rarer instances, the fugitives made it to the North from the Deep South states. They sometimes trekked more than a thousand miles, over hills, rivers, and mountains. They would sleep during the day, hiding out in dense woods, curled up in barns, outbuildings, or slave cabins. They traveled primarily at night to avoid the patrols. The North Star was their navigational guide.

In 1837 Charles Ball escaped from a South Carolina farm and headed north: He said, “From dark until ten or eleven o’clock at night, the patrol are watchful, and always traversing the country in quest of Negroes, but towards midnight, these gentlemen grow cold, or sleepy, or weary, and generally betake themselves to some house, where they can procure a comfortable fire.”

Sometimes, escapees from the Deep South stowed away on Mississippi steamboats and Atlantic coast vessels. Others posed as free blacks and boarded trains. William and Ellen Craft combined many of these techniques and ingeniously escaped from Georgia to Boston in 1848. Ellen, the daughter of her owner and very light-skinned, posed as her husband’s deaf and ailing master-her arm in a sling to cover her inability to write and her head wrapped in a bandage to camouflage her lack of a beard. Despite a near discovery in Baltimore, they reached their destination. Later, when two slave catchers appeared in Boston, they fled to Nova Scotia and eventually emigrated to England where they lived for 17 years. Ellen stated at the time, “I would much rather starve in England, a free woman, than be a slave for the best man that ever breathed upon the American Continent.”

The fugitives quickly found out that the North was not the “Promised Land;” rather, they were met there with discrimination and poverty, and found their dreams and hopes shattered. In southern Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, white residents held strong sympathies for the slaveholding South. They did little to assist runaways and had few qualms about turning them over to owners or slave catchers who came to claim them. African Americans’ social networks in the North were often family-and community-oriented. Many fugitives settled in black neighborhoods in Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Newark, and Boston.

In the 19th century, runaways could find help from the loosely organized anti-slavery advocates who became known as “conductors” on the Underground Railroad. The most outstanding of the black conductors was Harriet Tubman. She escaped slavery herself and led her family and hundreds of others to freedom during the course of 19 trips into the South. The network was especially active in the western territories after the War of 1812. By 1830 it had spread through 14 northern states. The network derived its name from the comment of a Kentucky slaveholder who had vainly pursued a fugitive into Ohio. He remarked that the man “must have gone off on an underground railroad.”

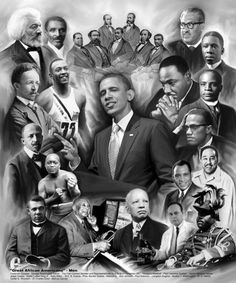

Quite a few fugitives in the North became active in the abolition movement. The most famous runaway, Frederick Douglas-one of the country’s greatest orators-was regarded by many, as the century’s leading abolitionist spokesman. Douglass’s writing and speeches gave an authentic voice to the abolitionist crusade.

Josiah Hanson, Anthon Burns, Samuel Ringgold Ward, William Wells Brown, Henry “Box” Brown, and others wrote about their experiences in slavery and became highly sought-after speakers on the anti-slavery lecture circuit. Their moving stories about their lives in bondage had a profound effect in converting northerners to the abolitionist cause. As historian Larry Gara wrote, “The eyewitness accounts of these former slaves had more impact in the anti-slavery cause than hundreds of theoretical speeches and pamphlets.”